The Casa Martelli museum is definitely worth a visit, especially for its precious rarities and the authentic atmosphere. Unlike many other museums, you will not find large groups of visitors here, which allows you to fully enjoy the authentic environment of the noble house.

Casa Martelli is a noble palace with a fascinating history, having been inhabited by the Martelli family itself from the 16th century until 1986. In that year, the last heir, Francesca Martelli, passed away at the age of 96 without leaving any direct heirs. Deeply religious, she donated the entire property to the church of San Lorenzo.

After her death, unfortunately, some very valuable items, not yet inventoried at the time, went missing. To prevent further loss of this important heritage, the Italian state purchased the house and its entire contents.

Despite its rich history, Casa Martelli is one of the most recent museums in Florence: it became state property only in 1999 and opened to the public in 2009. The mansion is the result of the progressive union of several houses acquired by the family since the 16th century, until it formed a complex as large as an entire city block, with an area of about 5,000 square meters.

Il piano terreno:

The first floor:

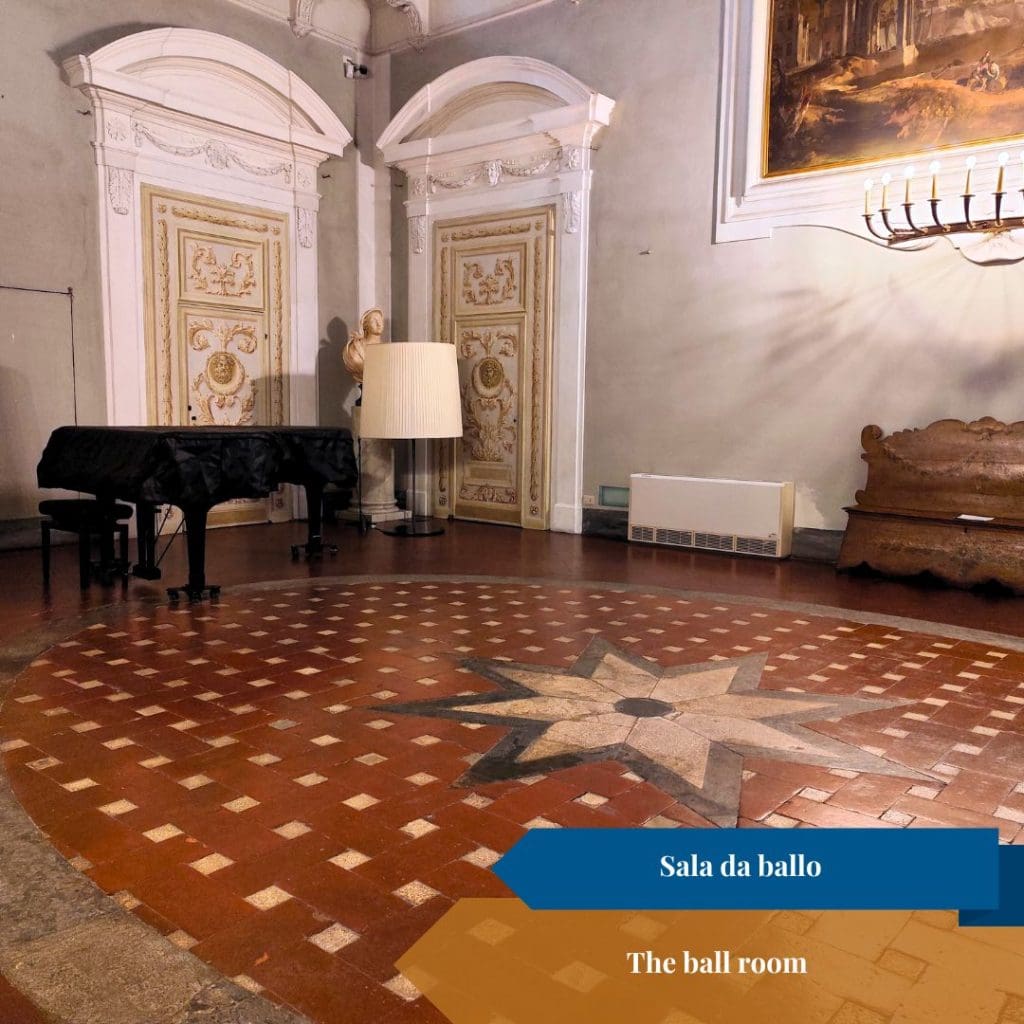

The “piano nobile”, that usually meant the first floor, represented the beating heart of any historic Italian palace. It was reserved for the residence of the owners, the most important family. These rooms, characterized by high ceilings, large windows and rich decorations, embodied the power and elegance of the household. The term “noble” comes precisely from its purpose: to house the “nobility,” or the most distinguished members of the family.

The family coat of arms

Upon entering the second floor of Casa Martelli, our gaze is immediately greeted by the family coat of arms, a gilded rampant griffin. The specimen we admire today is a replica, while the original, a testament to Donatello’s sculpture and therefore of particular value, is kept at the Bargello Museum.

Vigilance:

The ceiling of this room is richly painted, with a female figure dressed in white and yellow, an allegory of “Vigilance,” recognizable by the presence of a rooster, a symbol of alertness, at her side.

The picture gallery:

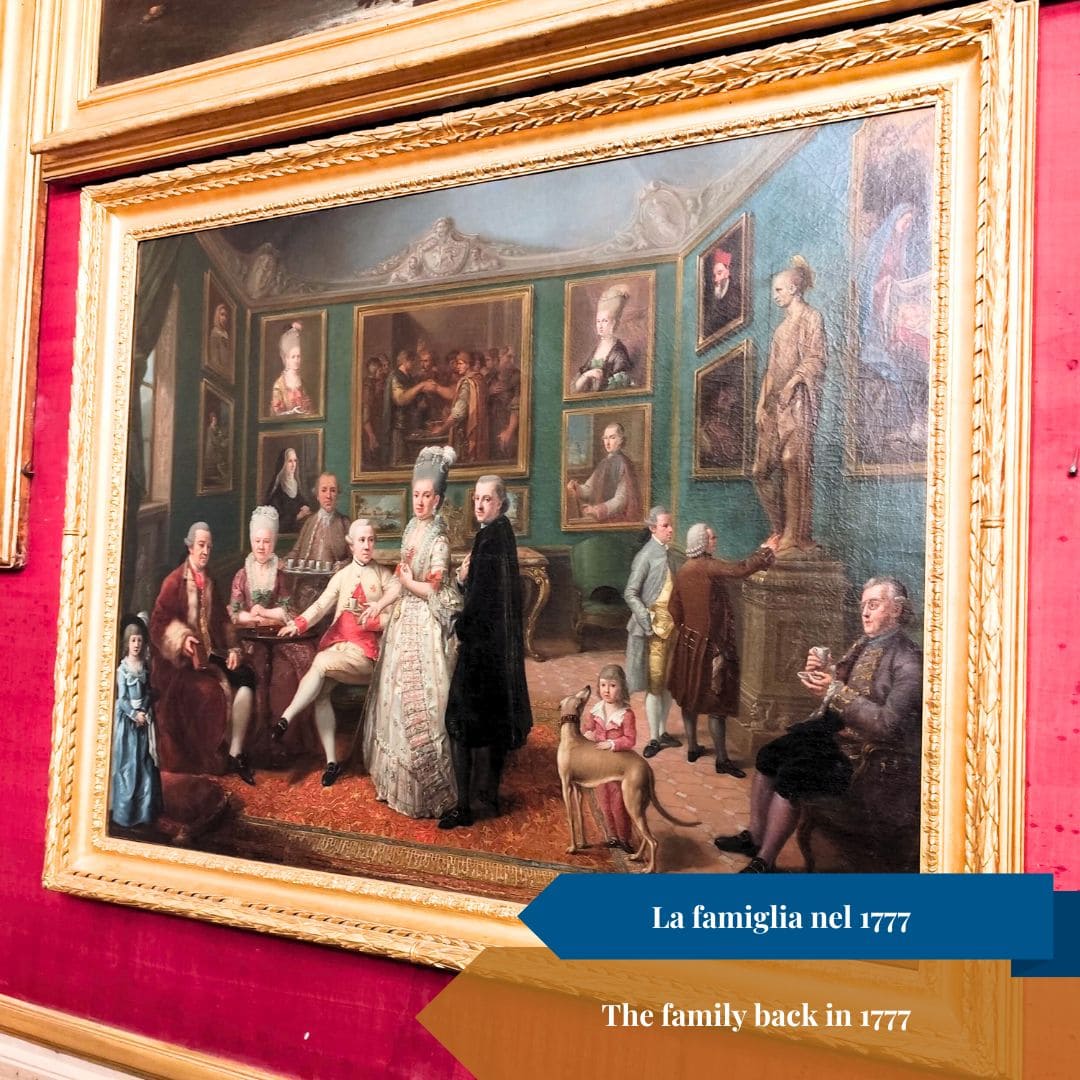

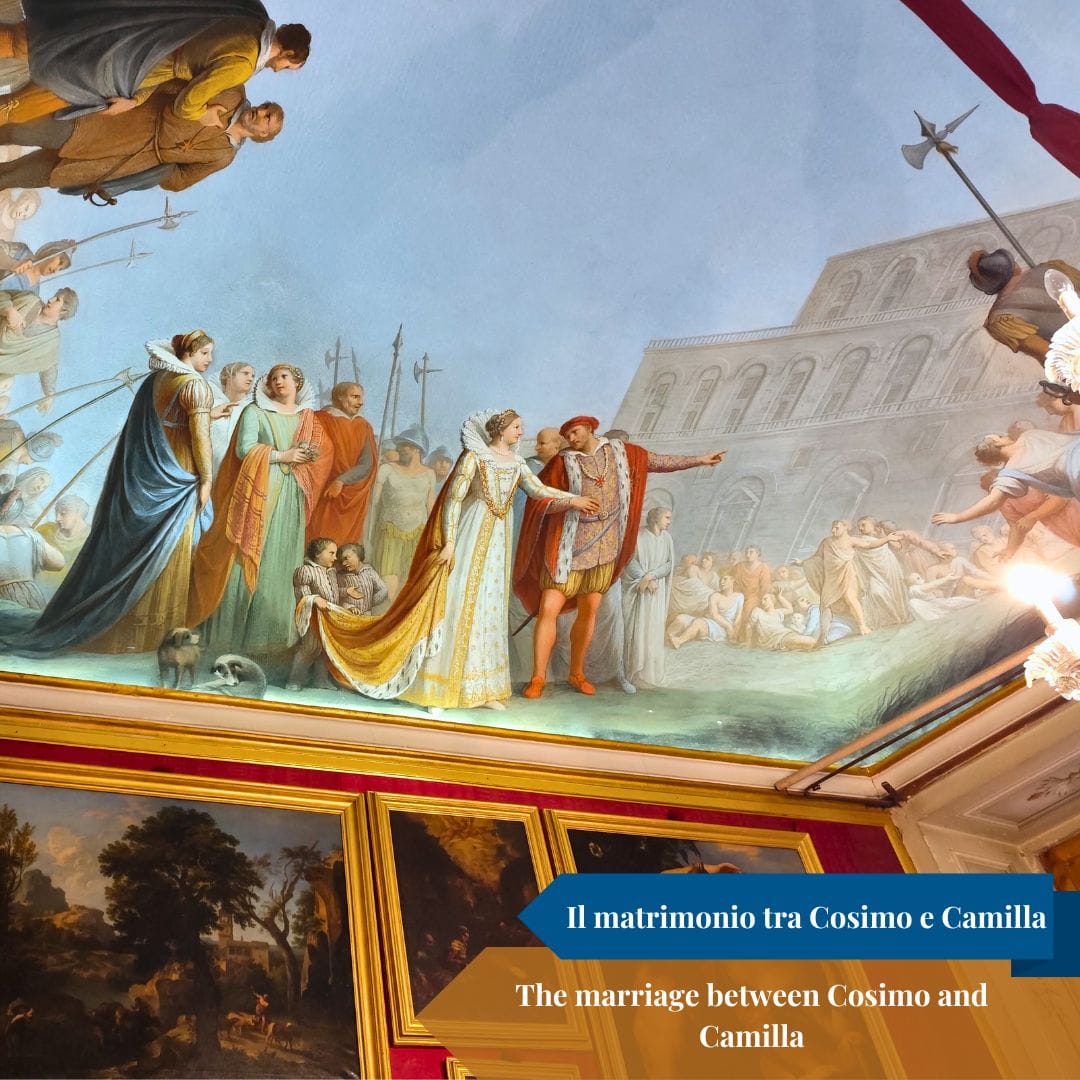

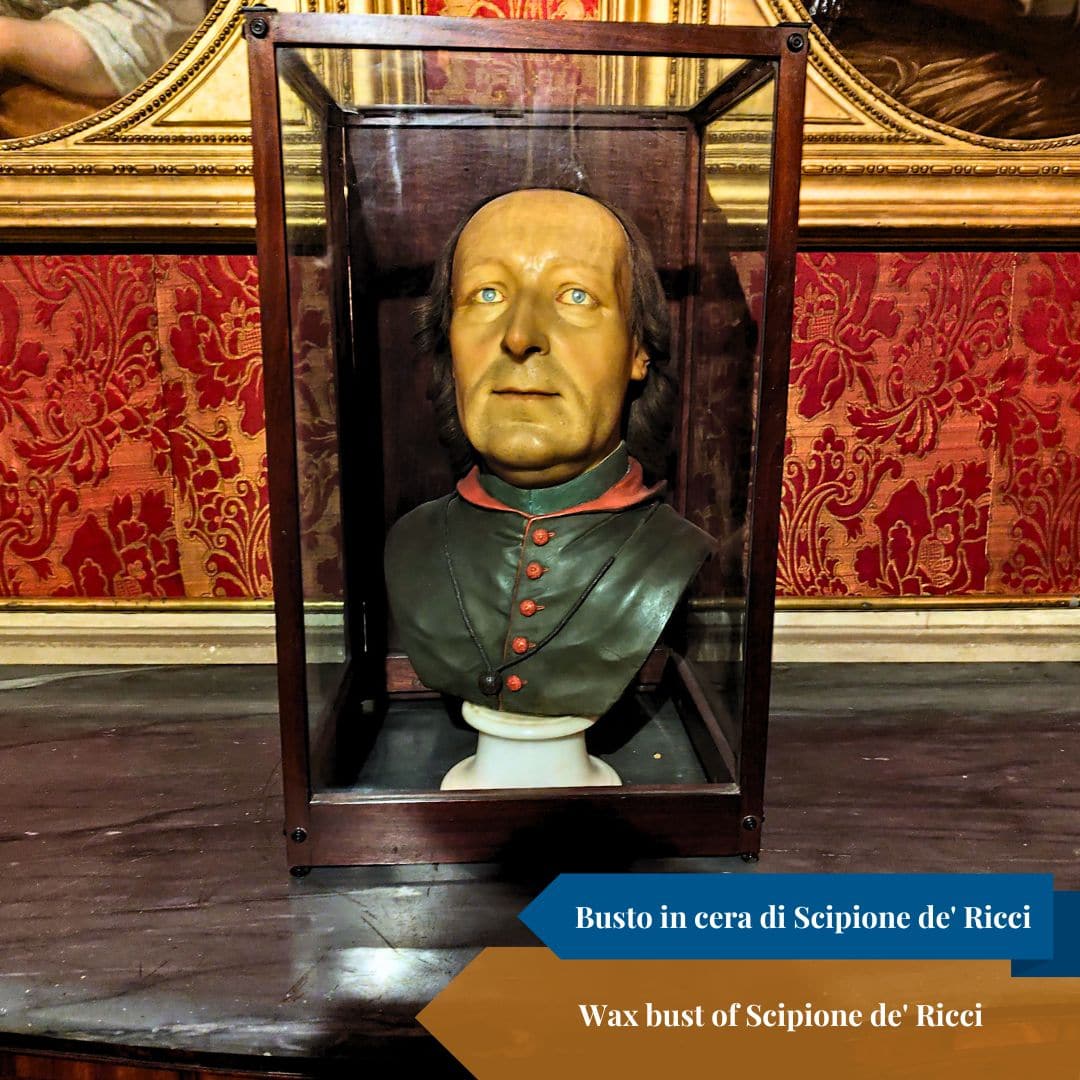

Continuing along the path on the second floor, we find ourselves immersed in the splendid collection of paintings that brings together works of immense value and from different eras. Prominent among the many paintings are portraits of key figures of the Martelli family.

The tour takes place in small groups of 15 people (max) and is led by museum staff.

Reservations are not required. Groups are formed at the museum entrance on a first-come, first-served basis.

Come and discover the beauties of Florence. Stay at our apartments!